This is a guest post by Prateek Choudhary, who is a good friend of mine. Prateek has extensive experience in working with startups and he will share some of his learnings in the epic post. So take it away Prateek!

Human beings are considered to be the most intelligent of all life forms. While philosophers, economists, and social scientists had assumed for centuries that human beings are rational, this is far from reality. It is not possible to make optimal and rational decisions every time due to constraints such as time and availability of data. So, we resort to mental shortcuts, also known as heuristics, to arrive at decisions- suboptimal but generally good enough to meet our needs.

Here is a comic that talks about our inherent biases.

Source: https://ichigoa.tumblr.com/post/25252699137

Let us take an example where our intuitions take over our rational decision making process:

A bat and ball cost a dollar and ten cents. The bat costs a dollar more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?

Take a moment and think about the answer.

The vast majority of people respond quickly, insisting the ball costs ten cents. This answer is both obvious and wrong. (The correct answer is five cents for the ball and a dollar and five cents for the bat.)

This is just one example of how biases influence our actions every day. These biases are shaped by our experiences and by cultural norms, and allow us to filter information and make quick decisions. We’ve evolved to trust our intuition. But sometimes these mental shortcuts can dupe us. And, smart marketers leverage these human biases very effectively in their strategies.

Listed below are 5 important biases that affect our decision making. These will help you understand why you make the choices you do and potentially help you avoid them and be more rational in your decision making process.

Table of Contents

1. Loss Aversion Bias

People generally tend to strongly prefer avoiding losses to acquiring gains.

Loss aversion is the wiring that makes us feel more depressed at the loss of Rs1000 than elated at winning the same amount of money. Data from Kahneman and Tversky suggests we prefer avoiding loss about twice as much as acquiring gains. Loss aversion also explains the endowment effect– the fact that people place higher value on something that they own than on an identical good that they don’t own.

Free subscription or trial periods are a great way to tap into this human anomaly. Once people use a certain product/service and have invested significant time on it, they start getting attached to it. In order to avoid losing it (since sentiments are involved now), they would most likely go for the paid subscription.

Another example is the presence of shopping bags/baskets in retail outlets. Once you place the potential purchases in your bag, you are psychologically tied to them and the longer you have them in your possession, the more difficult it becomes to let go of them.

What’s the reason we do not discard so many things in our house even though we haven’t used them in years or do not sell them at a loss?

The fear of losing them or the perceived loss associated with it.

2. Bandwagon effect

People tend to do something primarily because other people are doing it, regardless of their own beliefs, which they may ignore or override.

We are social animals and we like to belong in a group. We feel secure being on the majority and this leads us to conform to other people’s beliefs. ‘If so many people are doing it, they might be right’ becomes our basis for decision making. It’s psychologically easier to just agree with a popular notion. This is the reason why fads or trends are so common. People just hop on the bandwagon.

For example, in politics, people tend to vote for the most popular candidate or as shown by the media’s polls, because we like to be on the winning side or the majority.

Groupon is a great example of the “bandwagon effect”. Deals that pick up steam tend to accelerate even faster as the “bought” numbers increase.

Similarly, online reviews and ratings can significantly influence your decision making. If a product has on an average 4/5 stars from 1000 customers, it adds a lot of credibility to the product.

Another good example is Quora: An answer with a lot of upvotes tends to be upvoted more than the other answers. This phenomenon is also known as ‘herd mentality’.

3. Decoy effect or Asymmetric dominance

People will tend to have a specific change in preference between two options when also presented with a third option that is asymmetrically dominated.

Lets say we have two products A and B. We want to make the consumers buy product A. Such are the attributes of the products that in the absence of any other product, consumers would prefer to buy B.

So, what do you do now? The decoy effect comes into play. You introduce a third product A–, which is clearly inferior to A. In the presence of A–, people would start comparing it with A while B goes into oblivion. Hence, consumers are more likely to go for A because it appears to be the obvious best choice.

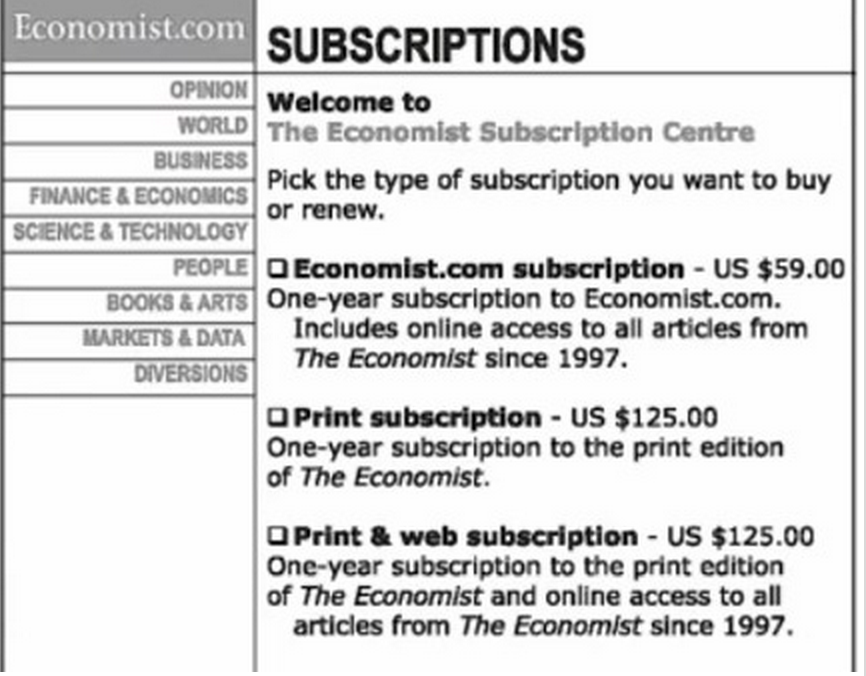

Let me illustrate this with the example of the Economist subscription page:

Spot the decoy in the above picture.

The middle option is the decoy (the A- as mentioned earlier)

Note how the “Print only” and the “Print + Web” subscriptions cost the same $125.

Who, in their right mind would pick the “Print only” option when you get online access for the same price?

Turns out that useless looking middle option plays a big role on how we choose.

Dan Ariely conducted an experiment at MIT where he had a set of students respond to the above ad. The results were:

Option 1 (web only): 16%

Option 2 (print only): 0%

Option 3 (print + web): 84%

Nothing very surprising about that result.

He then conducted the same experiment by removing the “useless” option 2, which no one picks anyway. The other two options remained the same. So the options were:

Option 1: Economist web subscription ($59)

Option 2: Print + Web annual subscription ($125)

Results:

Option 1 (web only): 68%

Option 2 (print + web): 32%

Apparently the “useless” option in the original ad makes option 3 (print + web) look way more attractive and drives our choices.

Source: Quora

4. Framing effect

People react to a particular choice in different ways depending on how the information is presented to them.

In Aldert Vrij’s book Detecting Lies and Deceit, he describes an interesting example:

Participants saw a film of a traffic accident and then answered questions about the event, including the question ‘About how fast were the cars going when they contacted each other?’ Other participants received the same information, except that the verb ‘contacted’ was replaced by either hit, bumped, collided, or smashed. Even though all of the participants saw the same film, the wording of the questions affected their answers. The speed estimates (in miles per hour) were 31, 34, 38, 39, and 41, respectively.

One week later, the participants were asked whether they had seen broken glass at the accident site. Although the correct answer was ‘no,’ 32% of the participants who were given the ‘smashed’ condition said that they had. Hence the wording of the question can influence their memory of the incident.

5. Anchoring Bias

People tend to give more weightage to the first piece of information available.

Also known as the relativity trap, it explains how humans are so bad at judging the absolute value of things and can process information easily with the help of an anchor- the first piece of information. Once an anchor is set, other judgements are made by adjusting away from that anchor, and there is a bias toward interpreting other information around the anchor.

For example, the initial price offered for a used car sets the standard for the rest of the negotiations, so that prices lower than the initial price seem more reasonable even if they are still higher than what the car is really worth.

Let us take another example: In one study, students were given anchors that were obviously wrong. They were asked whether Mahatma Gandhi died before or after age 9, or before or after age 140. Clearly neither of these anchors are correct, but the two groups still guessed significantly differently (choosing an average age of 50 vs. an average age of 67).

All of us exhibit some of these biases in our daily lives without even realising. As we grow older, these biases become more deep rooted and becomes part of our decision making process. Will we become completely rational once we know these biases? No way! It’s a lot of hard work. The law of least effort applies. Our automatic thinking is usually so successful, there seems to be no need to take every information into account every time. Its just not practical but what we can do is introspect, be aware of our biases, analyze the obstacles to rational behaviour and get around those obstacles before someone takes undue advantage of them.

I’ve known the existence of these for some time now. But they are very difficult to overcome.

Only way that I get to know that I was a victim of one of the biases is when introspecting a long past even while taking a walk.

Hopefully a remainder like this article help me be better prepared.

Thanks Prateek.